Posted on: 26th May 2022

By Tom Jameson

Guuranda, the Yorke Peninsula in South Australia, is a landscape of gently rolling hills, vast fields of grain stubble and dusty sheep. As you approach the coast, remnant patches of native shrub give way to sand dunes and mangroves, white sand beaches and an azure sea. At the very tip of the Peninsula lies Dhilba Guuranda-Innes National Park, a remaining swathe of native mallee bushland, made up of stringy bark gum-trees and silent salt lakes.

This is a beautiful but damaged landscape. Introduced foxes and cats have decimated populations of native animals, leading to the local extinction of most marsupial species. Large-scale land clearances have left only fragments of native habitat, scattered across the landscape.

There is a solution - the Marna (healthy/ prosperous) Banggara (Country) Project. This Project aims to restore the landscape of the Yorke Peninsula through rewilding, reintroducing locally-extinct native species to restore lost ecological processes. This approach benefits both the native landscape and agricultural productivity, as well as providing new economic opportunities for ecotourism in the area.

The Marna Banggara Project is a partnership between traditional owners (the Narungga, from whose language the project is named), farmers, NGOs, and government, with research being carried out to support the project by local and international Universities. Since on-ground work started in 2019, the project has made great progress. This includes erecting a 25 km anti-predator fence to enclose the 150,000 ha project area, intensifying control of fox and cat populations leading to the recovery of native animals and a decline in lamb mortality, and reintroducing the critically endangered brush-tailed bettong (Bettongia penicillata) to the region in 2021.

So where does a Cambridge PhD student come into this? As part of my PhD I’m researching the role that reptiles play in rewilding projects, so I’ve joined the Marna Banggara Project to investigate how reptiles can contribute to the Project’s goals.

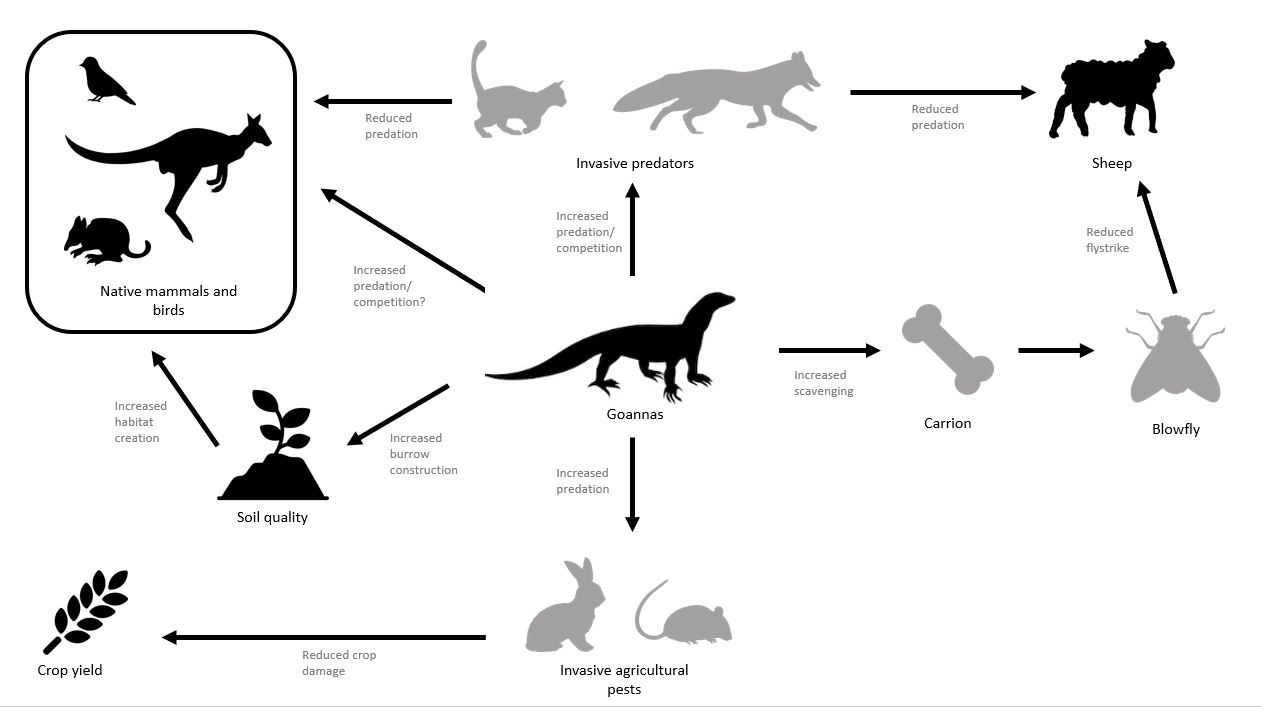

Within the Yorke Peninsula ecosystem the largest native predator and scavenger is a reptile, the heath goanna (Varanus rosenbergi), a species of monitor lizard growing up to 1.5 m long. Top predators provide important services to ecosystems by controlling populations of native species as well as reducing populations of invasive agricultural pests that can damage both native vegetation and crops. Scavengers also play an important ecological role in removing carcasses, supporting nutrient cycling and reducing the transmission of disease to native species, livestock, and humans. As such, the heath goanna is an important part of the Yorke Peninsula ecosystem.

However, to date very little is known about the heath goanna population on the Yorke Peninsula. I’m therefore conducting research to gather baseline population data on the Yorke Peninsula heath goannas, figuring out exactly where they are found and how many individuals remain. I’m also quantifying the services they provide to the ecosystem, carrying out field experiments to assess their role as predators and scavengers. The goal of all this work is to use the data I gather to build a management and rewilding plan for heath goannas as part of the Marna Banggara Project.

Working with the Project remotely from Cambridge, I used long term monitoring data to build a picture of goanna populations on the Peninsula. Invasive and native scavengers have been closely monitored across the area since 2014, using hundreds of baited motion-sensitive cameras. From these data I’ve been able to map the current range of the Yorke Peninsula goanna population.

Since February I’ve been lucky enough to be living out on the Yorke Peninsula, carrying out further research. I’m living right in the middle of Dhilba Guuranda-Innes National Park, in a cottage in the ghost town of Inneston, alongside kangaroos and emus. Inneston was a gypsum mining town abandoned in the 1930s. Over time, the town has slowly been swallowed up by the bush, with just a few houses preserved for use by researchers and tourists.

From this base, I’m conducting experiments to quantify the role of reptiles as scavengers. I’m using a series of feeding stations, baited with rat carcasses, that exclude different kinds of animals. By monitoring what species arrive with motion-sensing cameras, and recording removal of carcasses, I can quantify how important different groups of animals are as scavengers.

Preliminary results suggest that scavenging vertebrates are important for reducing incidence of disease from carcasses, with visits by scavengers to feeding stations reducing the number of harmful blowflies breeding in a carcass. Invasive predators like foxes are doing quite a lot of scavenging, so it’s important that replacements (like goannas) are in place as foxes are removed from the landscape.

My findings indicate that heath goannas are going to play an important role in the rewilding of the Yorke Peninsula. When it comes to rewilding, reptiles have often been overlooked and ignored in favor of mammals. As rewilding projects become more common in parts of the world with populations of large reptiles (like Australia), it is important that conservation plans account for the role that reptiles play.

More than anything else, the Marna Banggara Project is a project of hope. Against a global backdrop of catastrophic climate change, continued habitat loss, and mass extinctions, rewilding projects like Marna Banggara offer an alternative. Not content to just protect the fragments of remaining habitat left, rewilding projects push back, restoring ecosystems and healing environmental wounds. It’s been an absolute privilege to work on the Marna Banggara Project alongside inspiring scientists, land managers, and traditional owners. I’m looking forward to seeing the Project progress and the Yorke Peninsula becoming a little more wild, one lizard at a time.

Archive

2026

2024

July

June

2023

- Fantastic (mallee)fowl facts

- Malleefowl surprise for volunteers as count remains stable on previous year

- The bell tolls for native species with domestic cat spotted roaming

- Baby boom update from Marna Banggara

December

November

September

July

June

May

January

2022

- Rewilding reptiles: Using lizards to restore landscapes in South Australia

- Baby boom for first bettongs on Yorke Peninsula in over 100 years

December

November

July

May

March

2021

- Celebrating the return of brush-tailed bettongs to Yorke Peninsula

- Brush-tailed bettongs back on mainland South Australia after disappearing more than 100 years ago

October

September

August

July

April

2020

- Brush-tailed Bettongs: The habitat they like to call home

- The elusive Western Whipbird on song in Warrenben